Worldwide businesses, close ties with the most powerful world leaders, sophisticated conspiracies and a ton of money. That may sound like a fitting description for many members of the Richest Jews of 2017 list, but in fact, those lines briefly describe the life of Dona Gracia – the richest Jewish woman ever to live.

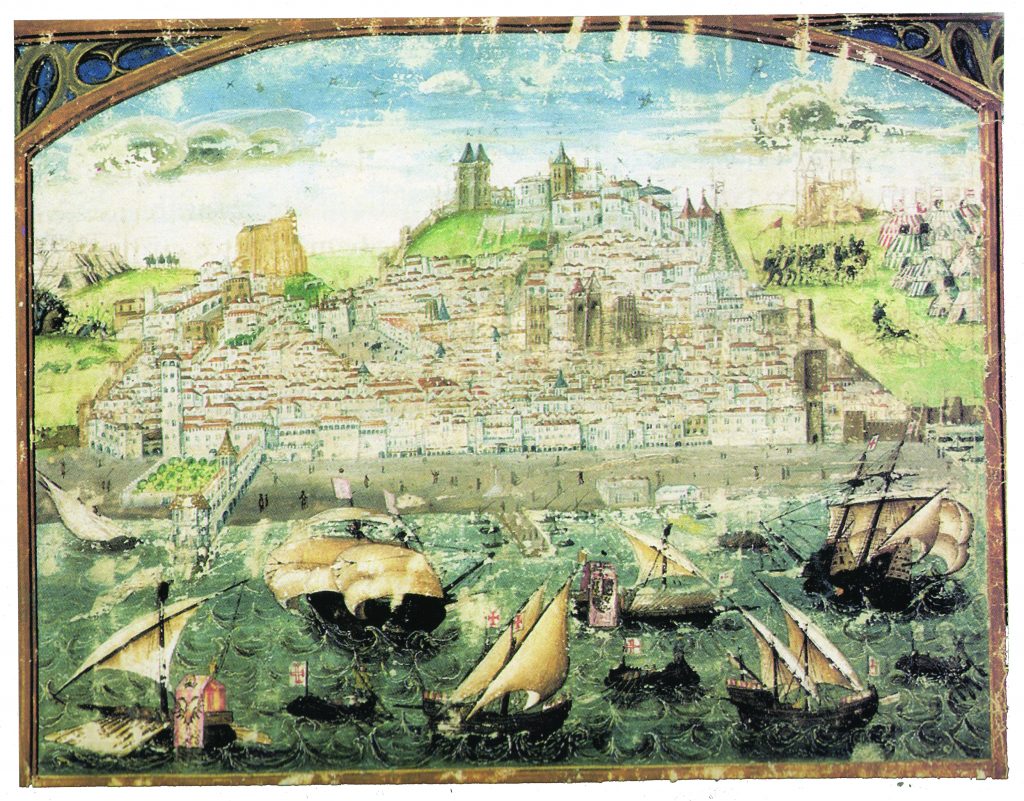

She was born in 1510 but her story begins nearly 20 years prior, in the crucial year of 1492. While Columbus’ ships were arriving for the first time to the shores of the New World, Ferdinand II and Isabella I, the Catholic monarchs of Spain, decided to expel Jews living in Castile and Aragon who refused to convert to Christianity. That fateful decision brought a swift end to the “golden age” of the Jewish community in Spain. Gracia’s family was one of those that successfully fled to neighboring Portugal, but even there, only a few years later, it was first decreed that all Jews should be expelled and later, forced to convert. These became the so-called ‘Marrano Jews’.

This was the reality that Gracia was born into, in Lisbon, by the name of Beatricia de Luna. At the age of 12, her parents revealed the family’s secret to her, and she began to learn Jewish customs. Six years later, she was married to her uncle Francisco Mendes, whose real name was Tzemach Benvenisti. He was the son of a family that dealt in silver, gems and spices, that had become especially wealthy thanks to that era’s “hottest” discovery – black pepper that was imported from India and became the status symbol of the nobility. Each year the Portuguese rulers granted the family the right to trade, which included money-lending by way of the Mendes Banking House, based in Antwerp (a city that became a primary place of refuge for Jews fleeing Spain), and that had ‘branches’ all over the world. When Francisco died, 9 years after they were wed, Dona Gracia was left, at the age of 27, with a huge fortune and a worldwide business empire.

Golden Clients

To illustrate the scope of Gracia’s enterprises and power during those years, one need only look at her clientele, which included the most powerful man in the world at that time – the Caesar of the holy Roman Empire, Charles V, who controlled Spain and considerable chunks of today’s Western Europe, the monarchs of England and France, the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and even popes.

Dona Gracia continued to nurture the trading enterprise, until she possessed a fleet of ships that surrounded the Portuguese-controlled islands, from the Cape of Good Hope to India. “In a way it was a business of entrepreneurship that she inherited and fostered”, says Naomi Keren, who researched the story of Dona Gracia for over a decade and authored the novel “La Senora” which is based on Gracia’s life.

“As a woman she was extremely unusual. In the 16th century, a woman was only able to be independent and manage her life as she wished if she had the legal status of widow. Before then she belonged to her father, her husband or her brother. Everyone expected that she would remarry and that her new husband would manage the money, but as far as it is known, she never re-married”.

Unfortunately for her, it was not simple to be a Jew, even if she presented as a Christian. The beginning of the Inquisition in Portugal eventually propelled her out of the kingdom, and she found herself setting out on a difficult and never-ending journey to save her family and her economic empire.

“The Marranos lived in a state of constant fear”, explains Keren. “The business with the money-lending was what saved her. She was always moving around the continent at the head of the family unit which included her, her sister, the daughters of each as well as those of their two nephews, plus a staff of around 30 servants, most of whom were also Marrano Jews. As a Jew, the safest way to move around was as part of a community. This was not an ideal lifestyle, but neither was it so dramatic as Gracia’s had once been – constantly deceiving and pretending while managing money and hanging onto it dearly”.

From Prison to Istanbul: Business in the 15th Century

Thanks to her connections in Antwerp, Dona Gracia managed to close her business interests in Lisbon, and set off by ship on a long journey which brought her to the Ottoman Empire. This was not easy. Before getting to Antwerp, she negotiated fiercely for permission for her ship’s passage through English shores.

In Antwerp, too, it quickly became clear that there was no safe place for Jews with a sizable fortune, and after the death of her brother-in-law, who left her his part of the family bank, she began to plan her escape. “Getaways were planned well in advance, as it was necessary to divert huge amounts of money from one country to another”, explains Keren. “When Carl V discovered that Gracia was fleeing to Antwerp, he sent agents to the ends of the continent in order to confiscate merchandise. For years the family was negotiating their return. It was a tremendous struggle”.

The next place Gracia moored was Venice, where she began to establish a low profile Jewish lifestyle while maintaining the outward Christian identity that protected her. But in Venice too, Gracia found no peace from her pursuers, and was already planning her escape to the Italian province of Ferrara, when an act of betrayal interrupted her plans.

Brianda, her sister, informed on Gracia’s Judaism, and both were arrested. The rift between the sisters sprung from the inheritance dispute that erupted with the death of Gracia’s husband, news of which reached one of the great rabbis, Rabbi Yosef Caro, who was required to decide the matter.

To be freed from her imprisonment, Gracia appealed to all the rulers to whom she had loaned money, but they saw her incarceration as a golden opportunity to evade repayment of their debts and they refused to hold up their end. It was her nephew that eventually helped her out of her situation, when he reached an agreement with the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, that obliged the Venetian rulers to release Gracia and not to interfere with her bank’s doings.

She left her Venetian palace and in Ferrara began to live a publicly Jewish life. She continued to fearlessly manage her affairs, and devoted her time to energetic activity in the Jewish world. Among other things, thanks to Gutenberg’s new invention, she established printing houses that published holy books and Jewish thought, as a corrective to the book burning of the Christian Inquisition.

A few years later she finally moved to the Ottoman Empire, far from the reach of the Inquisition. The Sultan warmly adopted the Jews and allowed the Marranos to return to practicing Judaism openly. He himself congratulated her on her arrival to Kostantiniyye (today’s Istanbul), and a royal ceremony was carried out in honor of Gracia and her retinue. She began to go by her original name – Hana Nasi, and together with her nephew, continued to use her vast network of connections with influential leaders in service of her lending enterprise.

Her arrival to Kostantiniyye reveals her profound power and influence, as well as her unconventionality, notes Keren. “Before relocating to the Ottoman Empire, she demanded and received permission to continue to wear the Venetian attire. Though it is a seemingly small detail, it is significant – it connotes an opinionated woman who stood her ground. She did not want to see herself in different dress. It even bordered on audacity to demand such a thing from a Sultan whose protection she needed, and nevertheless to demand. It illustrates her particular character and her independence in the world”.

Double Life

In her new home, Gracia did not have to fear the persecution of the Inquisition, and she set about helping many communities of Jews and Marranos. In that same period she managed, with great difficulty, to realize her late husband’s request to remove his bones from his grave in a Lisbon church, in order to have them buried in the Valley of Jehoshaphat in Jerusalem.

She opened synagogues and yeshivas and was involved in great works of philanthropy – many Marranos and Jews dined at her table. “The phenomenon of the Portuguese Marranos was unique”, explains Keren. “People converted to Christianity out of fear of pogroms and death, and once that fear diminished, they returned to Judaism. They were new Christians that converted but returned to a Jewish life. Meanwhile, however, if you converted, you couldn’t go backwards, you were under the Inquisition,” explains Keren.

“There were people who stopped believing. They became skeptical and impervious to religion. On the other hand, those that did believe lived in great fear. They had to publicly show that they were Christians. They would go to mass on Sunday, but mumble the prayer in reverse. Similarly, they could not outwardly enact the Jewish custom of bathing on Fridays. They would wait until the servants were not at home, but since they could not bring water from the well without servants, they had to make do with a damp cloth. Afterwards they would cover up their tracks so as not to be discovered.”

This double life made many Jews of the Iberian peninsula face impossible situations. “One of the senior advisors to the Spanish royalty was a Marrano and lived outwardly as a Christian at the same time as his family was being investigated in the Inquisition”, describes Keren. “His father was executed at the stake in front of him, and his wife was led in the procession of those condemned to death, some of whom had broken limbs. This man had to see the people closest to him in horrific circumstances and still continue to play the game.”

Insidehere home there was always fear that someone would take advantage of the concealed status, as had happened to Gracia when her sister denounced her in Italy. “They feared that the children might blurt something out. The assumption was that they would tell a child around the age of Bar Mitzvah that he or she was Jewish. Imagine a child like that, raised since birth by Christian servants, praying to the Virgin Mary, and then being told that everything they have known is a lie. One can guess what that does to a person’s soul. You can only count on yourself. With time, the connection to the Jewish roots become blurred, and the doubts and misgivings as to whether it is worth the price grow. In this sense, getting to the Ottoman Empire meant freedom, because there one could be who they were, and cast off their Christian persona. Of course mostly this was not done on account of fear for family relations who stayed behind”.

Economic Driving Force

Despite living in fear, the Marranos knew how to make money. The life they lived in the margins, neither here nor there, granted them the ability to move with social and economic freedom between different worlds, and to develop widespread business connections. Life on the fringes also sometimes pushed them to enter into new areas of business and to constantly seek out alternative income streams. “Jews were always good at languages, which was critical in the Iberian peninsula, in which there were both Christians and Muslims”, Keren notes. “This was not today’s global world of internet, although in certain respects these were global businesses. They would also conduct business with those they were in conflict with. Relationships existed on multiple levels, so even when there was friction on one level, it did not have to disturb business”.

According to her, starting in the 16th century, the Marranos, particularly in Portugal but also in the rest of Europe, created business networks so vast that they became the main economic power on which rested the economy that developed in Europe of modern times. These networks were typically based in port cities. This economic status partially protected the Jews, but it also brought additional persecution upon them. For example, at the end of the 15th century, the popes began to encourage migration of Jews to the port city of Ancona, which passed to the papal state, in order to develop its economy and to enable the city to compete with Venice. Until the middle of the 16th century, nearly 3,000 Jews lived in the city, among whom many were Marranos from Spain and Portugal. But in 1556, Pope Paul IV issued an order that overturned the policy regarding the Jews.

Their property was confiscated, they were placed in ghettos and forced to deny their Jewishness. Those that refused were taken to be executed. The events that shocked the Jewish community did not pass quietly by Dona Gracia, who declared an economic embargo on the city, an international destination for unloading goods. She came to an agreement with the prince of the city of Pizarro, according to which all merchandise destined for the port at Ancona would instead be brought to his city. The embargo created a divide within the Jewish communities, and although it appeared to close the Ancona port for a time, it eventually dissipated. Either way, that initiative established Dona Gracia’s status among European Jewry.

She was not merely a tycoon who enjoyed a luxurious life in her palace, but rather an admired figure. Thanks to her widespread activity, she was nicknamed “La Senora”. She operated an extensive network of agents who acted in secret to aid the Marranos Jews as they fled across Europe – much like a modern spy agency. Gracia’s agents even sent her ongoing reports on the economic and political goings-on in that period. The “headquarters” was in her home and moved with her every time she was forced to move from one place to the next.

Bank Mendes and its branches the world over assisted in secretly transferring money. In this way, Gracia was able to ensure that Jews would not lose their property as they were escaping. To this end, she developed a method for issuing promissory notes called Lettre De Change, which she herself used in order to preserve her fortune throughout her long journey.

Looking to the Future

After the failure of the embargo at Ancona, Gracia appealed to the Sultan and asked him to lease cities in the land of Israel, and he indeed leased for her or for her nephew (different documents provide conflicting evidence) the city of Tiberias, and some surrounding villages. Scholars are divided in their interpretation of Gracia’s motive – was she among the precursors of Zionism, 300 years before Herzl, or was it solely a financial motive.

Keren believes, according to an archive of letters of the Ottoman Empire, that this was a financial enterprise. “From the documents it is seen that Gracia was collecting taxes for the Sultan – from the fishermen and the people who came to the bathhouses in Tiberias, and in return he committed to grant a sum of money for the rebuilding of the city’s walls. From leaflets put out by the Italian Jewish community of that time, we know that it was written ‘Come on Mendes’ ships’.

There was an intention to establish the silk industry in Tiberias, alongside the existing textile industry in Tzefat. There are scholars who categorize her as zionist as their interpretation is that the leasing of Tiberias created an autonomous Jewish city. This is a far-reaching interpretation, in my opinion. If she had even thought of bringing people, they would presumably have been of her sort, with a double identity and that had always lived in fear. As such, it would seem that Gracia requested to build a refuge for those Jews that were persecuted in their own lands at that time. Tiberias was certainly a refuge for such people.”

Dona Gracia’s winding journey ended with her death in 1569 at the age of 59, apparently in Istanbul. “The great magic of her story”, concludes Keren, “is that on the one hand we know a lot about her and on the other hand there are a lot of blank spaces”. Her lofty status is known to us today thanks to the writings between world leaders of the time, along with preserved documents and certificates bearing their names. Despite the gap of more than 500 years since the days of Dona Gracia and today, she is still a subject of research around the world, and she and her family are immortalized in Israel – on stamps, special coins, and street names.

Translation from Hebrew: Zoe Jordan